Streetwear has never been just fashion — it’s a cultural statement, an expression of rebellion, and a dialogue between the streets and high fashion. From the origins of skateboarding in California to the experimental runways of Paris and Tokyo, streetwear has become a world movement that redefines itself every single day. Among the numerous brands that paved the way for this revolution, Comme des Garçons (CDG) stands out. Rei Kawakubo’s brand didn’t only have an impact on streetwear but also rewrote its visual code, bringing notions of imperfection, asymmetry, and conceptual richness to a previously logo-centric landscape.This article investigates how the story of streetwear can be narrated in terms of the development of Comme des Garçons’ design language, from its initial avant-garde beginnings to its close connection with the streetwear generation which currently reveres its heart logo and rebellious silhouettes.

From Counterculture to Conceptual Fashion

Streetwear emerged as a countercultural phenomenon created in the late 1970s and early 1980s by surf, skate, and hip-hop communities in Los Angeles and New York. It was all about authenticity and belonging — graphic t-shirts, sneakers, and hoodies that declared belonging. While this revolution began in the West, Rei Kawakubo was also reshaping fashion in the East. At the time officialcommedegarcons.com launched in Paris in 1981, Kawakubo stunned viewers with a collection commonly referred to as “Hiroshima Chic.” The shredded materials, mismatched hemlines, and somber color schemes were the exact antithesis of the sleek glamour that was sweeping European catwalks. Critics weren’t getting it — but this refusal of beauty standards became the seed of a new aesthetic revolution.

Like the first fans of streetwear, Kawakubo was rejecting perfection. She created a vocabulary in deconstruction, anti-fashion, and conceptual dressing. Her clothing wasn’t “streetwear” in the strictest sense — but it had the same anti-establishment vibe. Both movements embraced individuality over conformity — and that’s where their histories started to intersect.

The Genesis of CDG as a Streetwear Icon

By the late 1990s, streetwear had already crossed over with high fashion.

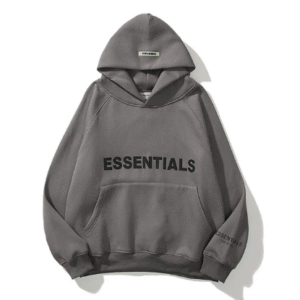

Supreme and BAPE introduced luxury within skate-inspired silhouettes, while Raf Simons and Jun Takahashi of Undercover infused youth culture into runway shows. Alongside this transition, Comme des Garçons became an anchor — a brand that both streetwear kids and fashion people respected. Then there was Comme des Garçons PLAY, which debuted in 2002. The label, with its now-iconic Filip Pagowski-designed heart logo, brought CDG into the hands of a new generation. PLAY connected the dots between avant-garde fashion and everyday street wear. The heart emblem printed on T-shirts, hoodies, and Converse shoes became an international streetwear icon — a discreet reference to those who could appreciate the deeper narrative surrounding it.So influential was PLAY, it wasn’t just branding that made it so. It was how it brought Kawakubo’s intellectual but minimalist personality into daywear. The clothes were plain — usually stripes or blocks of colour — but behind them lay a history of artistic defiance. To wear CDG PLAY was to make a statement of taste, intelligence, and subdued rebellion — not brash hype.

Collaborations When Concept Met Culture

Collaboration culture was one of the largest breaking points in the fusion of officialscommedesgarcons.com and streetwear.Well before it was a marketing buzzword, Rei Kawakubo saw partnerships as conceptual conversations. CDG worked with companies such as Nike, Supreme, Stüssy, Converse, and Vans, every time elevating utilitarian street items into works of art. The Comme des Garçons x Nike Air Force 1, for instance. The shape was still iconic and identifiable, but the trim — revealed seams, tone-on-tone contrasts, stacked materials — bore Kawakubo’s deconstructive signature. It was not merely a sneaker; it was an accessory to CDG’s design ethos. The CDG x Supreme collaboration in 2012 symbolized something even greater. Supreme, the streetwear king, and CDG, the avant-garde queen, stood together. The line blended skate culture graphics with deconstructed tailoring and polka dots — evidence that streetwear and conceptual fashion were no longer two distinct worlds but disparate dialects of the same visual language.These partnerships were a cultural cross-pollination: streetwear borrowed CDG’s intellectual sophistication, while CDG borrowed streetwear’s democratic appeal.

Deconstruction as Streetwear Language

Perhaps the most intriguing means by which CDG has influenced streetwear is through the democratization of imperfection.Prior to Kawakubo, fashion valued symmetry, fit, and finish. Post-CDG, imperfection was a design tool — a means to challenge conventional beauty and communicate individuality. Contemporary streetwear fully appropriates this concept. Oversized silhouettes, stitching visible from the inside, frayed hems — all are reminiscent of CDG’s deconstructionism. Vetements, Off-White, and even Yeezy owe some of their visual language to what Comme des Garçons initiated decades ago. Kawakubo’s creations reminded the fashion industry that clothes have stories to tell — that distortion, fragmentation, and asymmetry can evoke emotion the same way as color or pattern. Streetwear, which has always been a manifestation of individual expression, found its mirror in that ideology. It took CDG’s visual disorder and made it wearable dissent.

The CDG Uniform and Modern Street Aesthetic

In recent years, CDG’s imprint can be observed throughout the entire streetwear scene — from high-end drops to thrift-core chic. The CDG “uniform” — black layers, relaxed tailoring, and sneakers — is now a stealthy streetwear icon. It is the mature transformation of street style: minimalist, considered, yet effortlessly cool. Unlike traditional luxury, CDG’s appeal lies in restraint. Its followers don’t chase trends; they curate wardrobes around timeless rebellion. This is particularly evident in lines like CDG Homme Plus and CDG Shirt, which reinterpret everyday menswear with abstract proportions and bold graphic twists.Even the brand’s retail spaces, designed by Rei’s partner and architect Adrian Joffe, reflect this philosophy. Dover Street Market as an idea — half store, half gallery — became the focal point for the convergence of streetwear and high fashion, where brands such as Palace, Stüssy, and Gosha Rubchinskiy were co-located with CDG offerings. All this physical convergence cemented CDG as a cultural conduit.

Legacy The Streetwear Mindset Evolved

Now that we speak about streetwear, it is no longer simply hoodies and sneakers. It’s a mindset — one for which it prizes creativity, liberty, and upheaval. Comme des Garçons has all three. Rei Kawakubo’s professional calling has been to “create something that didn’t exist before” — and she continues to do so every time a new streetwear designer reinvents the game. The trajectory of streetwear itself — from subculture to luxury — might be read as CDG’s own trajectory: outsider misunderstood to culture leader. Both started out as rebellion and went on to redefine the mainstream. Both pushed against the way we think about fashion, beauty, and identity. As we continue further into an age when divisions disappear — between street and catwalk, minimalism and excess, digital and real — Comme des Garçons is evidence that fashion’s most experimental concepts tend to originate at the edges. Streetwear’s past isn’t narrated via sneakers or logos — it’s narrated through the vocabulary of designers such as Rei Kawakubo, who educated the world that rebellion can exist on an intellectual level, and that imperfection can be the most unadulterated form of style.